Dr. Weeks’ Comment: We have all heard the declaration: “Money makes the world go ’round” and so, logically, we can agree that money is powerful. So, hmmm…. perhaps we might imagine the following assertion: “In compassionate and sensible use of money is the salvation of the world.”

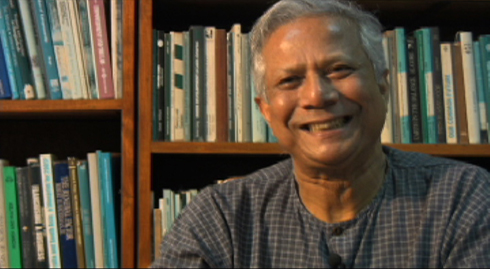

In contrast to the spiritually blinded bankers, let’s applaud Muhammad Yunus for his vision of the humane use of money.

| http://www.opednews.com/articles/The-Vision-of-Muhammad-Yu-by-Joan-Brunwasser-130413-504.html |

| April 13, 2013“The Vision of Muhammad Yunus” by filmmaker Holly Mosher

By Joan Brunwasser On April 17, Muhammad Yunus will be honored by Congress, becoming one of only seven people to ever achieve the trifecta: the Nobel Prize, the Presidential Medal of Honor and the Congressional Gold Medal. My guest today is Holly Mosher, award-winning filmmaker, director and producer of Bonsai People: The Vision of Muhammad Yunus. :::::::: On April 17, Muhammad Yunus will be honored by Congress, becoming one of only seven people to ever achieve the trifecta: the Nobel Prize, the Presidential Medal of Honor and the Congressional Gold Medal. My guest today is Holly Mosher, award-winning filmmaker, director and producer of Bonsai People: The Vision of Muhammad Yunus.

JB: Welcome to OpEdNews, Holly. What initially got you interested in this subject? HM: I had never heard of Muhammad Yunus or microcredit before I read the New York Times article announcing that he and the Grameen Bank had won the Nobel Peace Prize. There were two points in the article that just floored me: one, that he was helping 6.5 million women in Bangladesh, which I quickly realized was one out of every 1,000 people on earth, and two, that a banker and an economist had gotten the peace prize instead of the prize for economics. After reading that, I knew immediately that I had to go to Bangladesh and explore the possibilities for a film. I love seeing people make a positive difference in the world, and this seemed that it may be the biggest scope of positive impact I may ever see. JB: Why did he receive the peace prize as opposed to the prize for economics? HM: I think the person who puts it best is Mahatma Gandhi when he said, “Poverty is the worst form of violence.” I think the Nobel Committee has seen the impact that Muhammad Yunus’s work has had on lifting people out of poverty. When you look at the Grameen Bank’s index of poverty , they find that through the bank, over 50% rise above their level of poverty within 5-6 years. And one thing that made an impact on me is what Yunus said in his Nobel Peace Prize speech: “By giving us this prize, the Norwegian Nobel Committee has given important support to the proposition that peace is inextricably linked to poverty. Poverty is a threat to peace. The world’s income distribution gives a very telling story. 94% percent of the world income goes to 40% of the population while 60% of people live on only 6% of world income. Half of the world population lives on two dollars a day. Over one billion people live on less than a dollar a day. This is no formula for peace.” And I can say by what I witnessed in his work, that the struggle of those who truly are the poorest of the poor, they suffer from so many things that we can’t even imagine having to deal with in the 21st century. Shahnaj is a great example of the tragedy they face. Her son died from stepping on a chicken bone during the floods. He got tetanus and didn’t find out in time. They also had a roof full of holes, so when it rains everything get soaked and their floor turns to mud. They live in a single room with the goats in the kitchen during the storm. That people have to endure these conditions when the rest of the world has so much is a real tragedy and lack of balance in income distribution. When Yunus started his work, he was moved by the famine of 1974, which inspired George Harrison and Ravi Shankar to hold the Concert For Bangladesh. Hundreds of thousands of people were dying from hunger. That too, was actually a crisis of distribution. There was enough food, it was just not getting to the people that needed it most.

JB: Microlending flies in the face of conventional economic theory, doesn’t it? HM: It’s funny. When Yunus started, everyone thought he was crazy, because it hadn’t been done. They all assumed that the poor wouldn’t pay back because they don’t have money. Banks only lent to people who had collateral. But what Yunus saw was the opposite; in fact, the poor worked really hard so that they could pay back their loan. He just made the loan manageable by collecting small amounts each week, so that a big loan wasn’t hanging over their heads to be paid off all at once. Now, a lot of other groups see the potential for microcredit, but nowadays you have to be careful about what their motive is, and if they are running it in a way that really will benefit the poor. Some of them have gone public and that’s where I think they derail and stop putting what’s best for the poor first. There have been some serious abuses that need to be regulated within microcredit. But I think this will happen with any business idea; there is always room for abuse.

JB: Yunus’s approach was to look at conventional banks’ behavior and do just the opposite. Can you give some examples? HM: One of my favorite lines in the film is when Yunus says that he just looked at what the conventional banks did and he did the opposite. They lend to the men, he lends to the women; they lend to the rich, he lends to the poor; they work in the cities, he works in rural areas. Since he had not come from the banking industry, he was not stuck with their mentality of how things had to be run, so he was free to create his own system that worked on behalf of the poor. After all, his motive was to help save people from starvation, so the whole mindset around the work has been totally different from those working from a mindset of profit maximization. JB: Simple yet profound. Yunus has an unconventional view of the poor as well. According to him, poverty is the fault of an environment/society that has kept people from reaching their potential. HM: I think since Yunus is an economist and also a teacher, he was able to see things through a different lens than someone who had always been working in business. His first efforts at microcredit came by having his students work with him to try to help those suffering from the famine, so he went in with a researcher’s open mind. First, they tried to improve crop yields, but with that effort, when the day laborers came to do the husking, they told him that this didn’t really help them. It was then that he realized that the farmers were actually doing fine and that they needed to do something for the day laborers who were working so hard but living hand-to-mouth. They were the ones that needed help, so he decided to work with what he calls the poorest of the poor. These people work very hard, but they are at the mercy of job opportunities that come and go with the seasons. He also saw that they were often selling products in an indentured servitude way, for instance, where if they were making wooden stools, they would buy wood from the same person they sold them to and they were stuck paying the highest price for the raw materials and then getting the lowest price for their finished product. In the town they worked in, his students did the research and found that just $27 given to 42 people would get them out of this cycle. When they paid him back, his role in microcredit was born. Also, when you look at the lives of the poor, they often have to spend more time doing more work; they just aren’t benefitting from the higher salaries. One of the benefits often found through microcredit is the families finally have some leisure time. All of their effort isn’t put into where the next paycheck is coming from. I know I saw a lot of the poor in Bangladesh doing back-breaking work that we have machines to do here.

JB: It was predicted that Grameen would never collect on their loans to the lazy poor, yet the recovery rate has been an astounding 97%. HM: In creating what became the Grameen system, they had the groups meet every week and pay back a small amount. This really kept the loan manageable for the borrowers. On top of that, it gave them a support system. If anything is going wrong, others will know and help out, or offer advice and try to fix their problems. There is a lot of trial and error, as there is in any business, but by having group solidarity, they are able to have a very high rate of recovery. JB: Beyond microlending, Yunus also developed social business. How did this concept evolve? HM: Initially, Yunus began with microfinance, but immediately he saw that just as the poor lacked access to financial institutions, they also lacked access to so many other things that are basic needs, such as education, healthcare, energy, etc. From the beginning, they would have the borrowers pay a few cents to bring a teacher to the villages to help educate the people. Then, they began Grameen Shikkha as a separate company to provide education. As they studied why people couldn’t pay back loans, he saw that most people that couldn’t pay had health issues, which is not surprising because, in the US, over 60% of personal bankruptcies are also due to health issues, where you spend all your money trying to get better. So, they started a health company to try to prevent a lot of health problems that could be avoided with the right care. For example, he saw the kids suffering from night blindness. He asked doctors about why this happened and found it was simply due to a vitamin deficiency. So, he decided they should sell seeds and encourage everyone to plant their own kitchen gardens to take care of their nutritional needs. Not only did they become the largest seed seller in the country, but they were able to eradicate night blindness among children. Other groups may have come in and provided Vitamin A tablets to get rid of night blindness, but Yunus saw the power of using business solutions to really get to the root of the problem. So, he kept coming up with business solutions to solve these needs. And over time, he realized that he had created a business model which he now calls social business. Social business is a business created to solve a social or environmental need that is a non-loss, non-dividend company. The company wants to cover their costs to stay in business, pay decent salaries and grow, but they keep any profits in the company so what they can really do is help people have access to the things they need to live decent lives.

JB: Nice! Grameen now includes over 60 different social businesses. What can you tell me about how they work, Holly? HM: Here are his seven principles of social business:

Investors who invest in a social business get their initial loan back, but interest-free. So, it is a way to recycle their charity. JB: Where did all these ideas come from? HM: This idea came about as he was trying to help the people he was working with. At first, it wasn’t more than just solving problems in a very straightforward business way. He was providing services that a new government with a huge population – and a significant number of those deeply impoverished – could not do. I don’t think he had a word for it until he was visiting France in 2005 and the head of Danone, Frank Riboud, invited him to lunch. It was during lunch that the idea of Grameen Danone was born. At the meeting, Yunus proposed that Danone would put up the money to start a venture in Bangladesh to help the malnourished children. They would help create the product, do the research and work together to run it. They ended lunch with a deal in place. He called Mr. Riboud the next day to make sure they were clear on the terms, because he wasn’t certain that Mr. Riboud had really wanted to agree to creating a business that would bring Danone zero profit. Mr. Riboud assured him that he had understood perfectly. Since then, Yunus has written two books* on the topic and formalized the idea. His version of social business is quite strict in that investors should get zero profit from the company. And I wouldn’t be surprised if he draws such a firm line in the sand because he’s seen so many microcredit groups start off with good intentions, but then have veered off to charge higher interest rates than even the money lenders he was trying to get away from. He wants to make sure that social business stays pure so that it can not be greenwashed. A lot of people think that social business may be more complicated than other business but, in reality, these are all just really simple solutions. And, since you don’t have to focus on profit maximization to make your investors happy, you can just focus on what your clients need. The biggest challenges are probably getting the initial investment and then figuring out efficient ways to scale. And certainly, in Bangladesh, because of the large population of impoverished people, they have a large clientele, which allows for such growth.

JB: Let’s take a break here, Holly. We’ll have lots more to talk about in the next two installments of this interview. Readers, I hope you’ll join us. *** Mosher’s website Watch the trailer for Bonsai People: The Vision of Muhammad Yunus Books by Muhammad Yunus: Building Social Business: The New Kind of Capitalism That Serves Humanity’s Most Pressing Needs [May 2010] Creating a World Without Poverty: Social Business and the Future of Capitalism [January 2009] Banker To The Poor: Micro-Lending and the Battle Against World Poverty [October 2003] Thank you, Meryl Ann Butler, for your help on this |