Dr. Weeks’ Comment: the time has come to trim this elephant in the room down to size. Let the system allow the consumer to hold the producers accountable – Rx free market system. (Note the third article below puts faith in the government to hold down prices – a fantasy which despite being well-articulated, has never been an optimal solution.).

The High Cost of Care

For the first time in our history, we are devoting the entire feature section of the magazine to a single story by one writer: a powerful examination of America’s health care costs. The 24,105-word story, reported and written by Steve Brill, inverts the standard question of who should pay for health care and asks instead, Why are we paying so much? Why do we spend nearly 20% of our gross domestic product on health care, twice as much as most other developed countries, which get the same or better health outcomes? Why, Brill asks, does America spend more on health care than the next 10 highest-spending countries combined?

One answer is that health care is a seller’s market and we’re all buyers–buyers with little knowledge and no ability to negotiate. It’s a $2.8 trillion market, but it’s not a free one. Hospitals and health care providers offer services at prices that very often bear little relationship to costs. They charge what they want to, and mostly–because it’s a life-and-death issue–we have to pay. Have you actually looked at your hospital bill? It’s largely indecipherable, but Brill meticulously dissects bills and calculates the true costs. He employs a classic journalistic practice: he follows the money, and he does it right down to the 10,000% markup that hospitals put on acetaminophen. He explains why about one-fourth of our bloated health care spending is overpayment and strips the veneer from of a vital American industry that is not always what it seems to be.

Brill, the founder of Court TV and American Lawyer and the CEO of Journalism Online, is one of America’s premier–and most dogged–journalists. Brill, who will be talking about health care on CNN all this week, has worked on this story for the past seven months. “What I learned in doing the piece,” he says, “is what I always tell my journalism students: opinions and policy debates are boring and meaningless without looking at the facts, without doing the grunt work of real reporting.”

If the piece has a villain, it’s something you’ve probably never heard of: the chargemaster, the mysterious internal price list for products and services that every hospital in the U.S. keeps. If the piece has a hero, it’s an unlikely one: Medicare, the government program that by law can pay hospitals only the approximate costs of care. It’s Medicare, not Obamacare, that is bending the curve in terms of costs and efficiency. Brill’s story is resolutely nonideological, but it resets the terms of one of our most important policy debates. Both sides of the aisle are culpable, as our elected leaders refuse to rein in hospitals and health care providers. According to Brill, there are things that can be done. He argues that lowering the age of Medicare entry, not raising it, would lower costs. And that allowing Medicare to competitively price and assess drugs would save billions of dollars. Asking wealthy Medicare recipients for higher co-pays would make sense. Most of all, health care must be a market in which patients can help control costs by understanding them better. And make sure you look at your hospital bill.

Read more: http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,2136867,00.html#ixzz2c0lZPWMV

From NYT 3-17-13

Time’s Health Care Opus Is a Hit

By CHRISTINE HAUGHNEYPublishing a 36-page cover article called “Bitter Pill: Why Medical Bills Are Killing Us” certainly didn’t seem like a shameless attempt to bolster newsstand sales for Time magazine.

But the 25,000-word article that Steven Brill wrote for the magazine’s March 4 issue appears to be on course to become its best-selling cover in nearly two years. Ali Zelenko, a Time spokeswoman, said the issue sold more than double the typical number of copies.

It was outperformed only by Steve Jobs, Osama bin Laden and special issues of Person of the Year and the royal wedding. It also broke online records, selling 16 times more than an average week for digital single copy sales and digital subscriptions and becoming the most viewed magazine cover article on Time.com.

The managing editor, Richard Stengel, expressed relief at the response.

“Was I worried it would not be the world’s greatest hit? Yeah. It’s really struck a nerve and captured lightning in a bottle,” he said. He added that the response also indicated that long-form journalism was still in demand.

The most surprising attention came from younger readers on social media who are less immediately concerned with medical bills. The article was shared 100 times more often on social media than the average Time article in 2013, and the #BitterPill hashtag was mentioned nearly 6,000 times on Twitter.

One reader wrote on nytimes.com, “This is the only time in my life that I have been interested in buying Time magazine. I’m 30. I’m unsure whether this bodes poorly for them, or well. Maybe I’ll find something I like and give it a chance?”

Mr. Brill said he was still receiving 50 e-mails a day from readers, and that many of those readers were in their 20s. His appearance on “The Daily Show With Jon Stewart,” he said, seemed to help increase his readership among a younger audience.

“These people in their 20s really care about this stuff,” said Mr. Brill, who added that at least one reader disclosed the costs of his hospital bills when he was injured riding his bike in New York City.

FROM THE WASHINGTON POST

Steven Brill’s 26,000-word health-care story, in one sentence

By Sarah Kliff, Published: February 23 at 1:10 pmE-mail the writer

Steven Brill started his cover story in this week’s Time magazine with a simple health-policy question: “Why exactly are the bills so high?”

His article is essentially a 26,000-word answer, the longest story that the magazine has ever run by a single author. It’s worth reading in full, but if you’re looking for a quick summary, the article seemed to me to boil down to one sentence: The American health-care system does not use rate-setting.

Much of Brill’s piece focuses on the absurdly high prices that hospitals and doctors charge for the most mundane items. A single Tylenol tablet can cost $1.50 when “you can buy 100 of them on Amazon for $1.49 even without a hospital’s purchasing power.” One patient gets charged $6 for a marker used to mark his body before surgery. Another is billed $77 for each of four boxes of gauze used.

One hospital, according to Brill’s math, bills $1,200 per hour for one nurse’s services.

“Over the past few decades, we’ve enriched the labs, drug companies, medical device makers, hospital administrators and purveyors of CT scans, MRIs, canes and wheelchairs,” Brill concludes. ”Meanwhile … we’ve squeezed everyone outside the system who gets stuck with the bills.”

In other countries, that cannot happen: Their federal governments set rates for what both private and public plans can charge for various procedures. Those countries have tended to see much lower growth in health-care costs.

What sets our really expensive health-care system apart from most others isn’t necessarily the fact it’s not single-payer or universal. It’s that the federal government does not regulate the prices that health-care providers can charge.

You can see this in Luxembourg, which had the lowest health-care cost growth ”” 0.7 percent ”” of any OECD country in the 2000s. Its system allows patients free choice of what doctor to see or what hospital to visit but has the government set all rates for what doctors get paid for those visits.

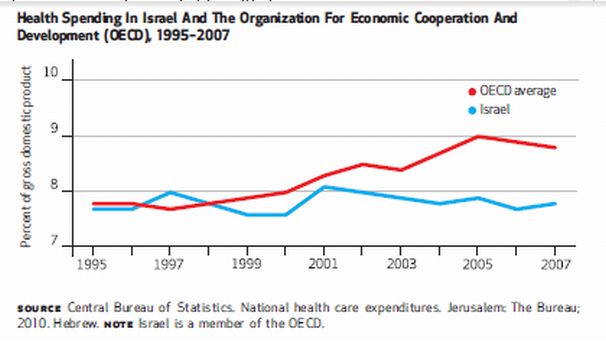

Or look at Israel, which has also beaten the OECD average:

Here’s how its system works, per the academic journal Health Affairs:

Here’s how its system works, per the academic journal Health Affairs:

The national government exerts direct operational control over a large proportion of total health care expenditures, through a range of mechanisms, including caps on hospital revenue and national contracts with salaried physicians. The Ministry of Finance has been able to persuade the national government to agree to relatively small increases in the health care budget because the system has performed well, with a very high level of public satisfaction.

Germany uses rate-setting, and its health-care costs grew, on average, 2.0 percent annually in the 2000s. France sets rates, as does Switzerland. All three countries have seen slower cost growth than the United States ”” although it’s worth noting that the United States actually saw slower growth in the 2000s than the OECD average.

In none of the countries with the lowest health-care costs can doctors charge $1.50 for a single Tylenol pill or $77 for a box of gauze. Many studies suggest that is a key reason why their costs have grown more slowly than ours.

It turns out that we don’t even have to go oversees to see this: Maryland has succeeded in controlling costs for about four decades now. It is the only state that sets rates for hospitals, with the state government deciding what every Maryland hospital can charge for a given procedure..

That system started in 1976, when Maryland had hospital costs 26 percent higher than the rest of the the country. In 2008, the average cost for a hospital admission in Maryland was down to national levels. ”From 1997 through 2008, Maryland hospitals experienced the lowest cumulative growth in cost per adjusted admission of any state in the nation,” the state concluded in a 2010 report.

Rate-setting is not popular here. About 30 states implemented schemes similar to Maryland’s in the 1990s but have since repealed them. The heavy-handed regulation proved unpopular, so states shifted toward managed care as a means of cost control.

There could certainly other factors at play: As Brill points out, for example, the American health-care system encourages higher spending by paying doctors a fee for every service they provide. Still, Americans actually go to the doctor less than residents of other countries, as the Commonwealth Fund found in an analysis last year.

The thrust of the piece, though, is all about prices. And that’s one area where we know what a solution might look like. In a way, the success of rate-setting makes simple sense: When the government has the final say on how much a medical procedure costs, it’s not that hard to hold down the price.