The Scan That Didn’t Scan

This is a story about M.R.I.‘s, those amazing scans that can show tissue injury and bone damage, inflammation and fluid accumulation. Except when they can’t and you think they can.

Related

Health Guide: M.R.I. »

Audio

David Corcoran, a science editor, explores some of the topics addressed in this week’s Science Times.

![]() Podcast: Science Update (mp3)

Podcast: Science Update (mp3)

RSS Feed

I found out about magnetic resonance imaging tests when I injured my forefoot running. All of a sudden, halfway through a run, my foot hurt so much that I had to stop.

But an M.R.I. at a local radiology center found nothing wrong.

That, of course, was what I wanted to hear. So I spent five days waiting for it to feel better, taking the anti-inflammatory drugs ibuprofen and naproxen, using an elliptical cross-trainer, and riding my road bike with its clipless pedals that attach themselves to my bicycling shoes. By then, my foot hurt so much I had to walk on my heel. I was beginning to doubt that scan: it was hard to believe nothing was wrong. So I went to the Hospital for Special Surgery in New York for a second opinion from Dr. John G. Kennedy, an orthopedist who specializes in sports-related lower-limb injuries. And there I had another M.R.I.

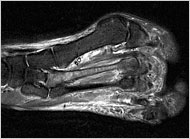

It showed a serious stress fracture, a hairline crack in a metatarsal bone in my forefoot. It was so serious, in fact, that Dr. Kennedy warned that I risked surgery if I continued activities like cycling and the elliptical cross-trainer, which make such injuries worse. And I had to stop taking anti-inflammatory drugs, since they impede bone healing.

As I hobbled around the office on crutches, one of my colleagues, James Glanz, asked what had happened. As we chatted, it turned out that he had had a much more sobering experience than mine.

Jim, the Baghdad bureau chief for The New York Times, was playing touch football in New York in late 2005 when he landed hard while diving to make a catch, both elbows hitting the ground at once. The next day, his fingers and hands hurt so much he couldn’t type.

But an M.R.I. showed nothing except some bulging disks in his neck that, he was told, were common in people his age, 50. He was advised to do neck exercises, and eventually he felt better.

About a year later, he fell again while playing football. His symptoms came roaring back.

The worst was when he woke up in the morning, Jim said. The two middle fingers on each hand were so stiff they would not even bend. He would massage his fingers and loosen them, but his hands and knuckles ached all day. He tried ibuprofen, to little avail.

Finally, last spring, he sought help at New York University, where he had another M.R.I. It turned out he had a nerve impingement so serious that he was warned that he risked permanent paralysis if he did not have surgery. So this summer, he had a major operation called a French-door laminoplasty, in which his surgeon, Dr. Ronald Moskovich at the N.Y.U. Hospital for Joint Diseases, opened and widened four or five vertebrae to free the trapped nerves.

How could M.R.I.’s have come to such different conclusions for both Jim and me?

Jim asked his doctors whether he could have really had nothing wrong at the time of his first scan. Unlikely, they replied, although they cautioned that no one had directly compared the two scans.

I asked Dr. Kennedy the same question and received the same answer. He explained that in my case the quality of the two images was vastly different. “It’s like the difference between a black-and-white TV and HDTV,” he said.

All well and good, but how was I supposed to know? The radiology center I first went to is accredited by the American College of Radiology, and there is no way I can tell a good M.R.I. image from a bad one. In fact, I never even saw the images. All I saw were the radiologists’ reports.

Academic radiologists say that, unfortunately, they see patients like Jim and me all the time.

“That’s the bane of our existence in an academic medical center,” said Dr. Howard P. Forman, a professor of diagnostic radiology at Yale University School of Medicine.

And it’s not just patients who have to deal with the problem, said Dr. William C. Black, a professor of radiology and community and family medicine at Dartmouth Medical School. Doctors do, too. Radiology centers send written reports to doctors, but the doctors may have no idea whether the M.R.I. was done well and interpreted well. “It’s a huge problem,” Dr. Black said.

Unlike C.T. scans or X-rays, which transmit radiation through the body to produce images, M.R.I.’s use powerful magnets and radio waves to manipulate protons in the body’s hydrogen atoms. The idea, said Dr. Andrew H. Haims, a diagnostic radiologist at Yale, is that protons in different types of tissue respond in distinctive ways to this pushing and prodding. The differing responses reveal the characteristics of the tissue.

Magnetic resonance machines, though, vary enormously, and not just in the strength of their magnets. Even more important, radiologists say, is the quality of the imaging coils they put around the body part being scanned and the computer programs they use to control the imaging and to analyze the images. And there is a huge variability in skill among the technicians doing the scans.

Related

Health Guide: M.R.I. »

Audio

David Corcoran, a science editor, explores some of the topics addressed in this week’s Science Times.

![]() Podcast: Science Update (mp3)

Podcast: Science Update (mp3)

RSS Feed

Dr. Forman said that at the very least, patients should go to radiology centers accredited by the American College of Radiology. But he added that accreditation does not tell you whether your scan will be done with a machine that is several generations removed from the best available today; whether the scanning is programmed to pick up your particular problem; or whether the receiving coil that picks up signals from the magnet is sufficiently sensitive.

G. Scott Gazelle, a professor of radiology at Harvard Medical School, shared Dr. Forman’s opinions.

“People don’t understand that there are these differences,” he said, adding that radiology centers that do not keep up will be doing a less than ideal job. “The pace of technology development is staggering,” he said.

Then there is the question of how skilled is the radiologist who reads your scans.

At Massachusetts General Hospital, for example, Dr. Gazelle said, “musculoskeletal M.R.I.’s are read by someone who does musculoskeletal imaging every day” ”” and not “by someone who reads chest M.R.I.’s one day and musculoskeletal M.R.I.’s the next.”

Dr. Forman says it pays to check the credentials of a center’s radiologists.

“If you say, ”˜Who will be reading my scan?’ and they say, ”˜One of our radiologists,’ you don’t go to a place like that,” he said. (I checked the Web site of the first center I went to. The radiologist who read my scan was a generalist with no special training.)

Of course, it may not be feasible to go to an academic medical center where subspecialists will read your images. And even if you do, said Dr. James Thrall, chairman of the board of chancellors of the American College of Radiology, “scans, as good as they are, are not perfect.”

”I wouldn’t equate a negative scan as being an 100 percent indicator that nothing is wrong,” he added. So if you are told nothing is wrong because a scan was negative and you are having alarming symptoms, you may want to seek a second opinion.

And don’t forget, said Dr. Jeffrey Jarvik, a professor of radiology and neurological surgery at the University of Washington, the point of an M.R.I., or any imaging study, is to help make a diagnosis that will improve your health. Often imaging is unnecessary: a good exam will reveal what’s wrong, and the treatment will be the same with or without the scan.

Just as big a problem as the erratic quality of scans is the tendency of doctors and patients to rely on them too much.

“There’s been a shift in medicine toward relying on imaging instead of a history and examination,” Dr. Jarvik said.

And I suspect that that was one reason Jim and I were so misled.

“Pain is a way for Mother Nature to talk to us,” Dr. Thrall told me. “And when our invented process for understanding is at odds with what Mother Nature is telling us, we had better listen to Mother Nature.”